Painting the Edge: Where the Planet Meets the Sky

The Zen Vision of the late Louisiana Painter Elemore Morgan Jr.

Dear Spark Zen Readers, I hope you’re each doing well today. This Sunday post varies from my usual offerings in that the words “Zen” and “Buddhism” are not mentioned. This is because I wrote it in 1998 before I began practicing Zen when I was a graduate student earning a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing in southwest Louisiana.

During my three years in Louisiana, I had the great, good fortune to meet the fabulous painter and extraordinary human Elemore Morgan, Jr., who died in 2008. I wrote two stories about him: the first was about surviving cancer and the second was about his passion for painting the prairies and rice fields of Southwest Louisiana. I never got this story published as I only submitted it to one literary journal and they thought it wasn’t literary enough.

After a recent email exchange with

, I learned that Jeff is a fan of Elemore’s paintings. In homage to Elemore and in admiration of Jeff’s electric and captivating art, I’m sharing this story about spending time with Elemore while he “painted the edge of the planet as it met the sky.” I’m sure you’ll find the “Zen” in Elemore’s love for and respect of Nature. Bowing from where the creek meets the mountains, Rev. Shōren Heather“Bring your boots. Sometimes it gets muddy out here.” That’s the only advice Louisiana artist Elemore Morgan Jr. gives me during a telephone conversation about our meeting to discuss his open-air (en plein air) style of painting.

On my first visit to Morgan’s house a week later, I brought my boots. Tan, synthetic leather Wal-Mart specials that blister my big toes and ankles when I wear them. A small price to pay considering they cost only $14.99. (Nothing’s cheap enough when you’re a graduate student.)

As a graduate student living in Lake Charles, Louisiana, my world was small. It encompassed four square miles of the city with the campus, my apartment, the supermarket, the laundry place, and the discount cinema serving as alternate centers of my universe. So the prospect of traveling outside these boundaries and meeting someone who was not a classmate, a student, or an English professor moved me to drive the 60 miles to Lafayette one sunny, cool November day.

Before I met Morgan, I had never heard of him or his paintings or any of the rural towns that comprise the ten square miles of Louisiana territory where Morgan finds his muse: Leroy, Kaplan, and Maurice. Since the early 1960’s, Morgan has drawn inspiration from the terraced rice fields, towering skies, and iridescent light of the prairie lands just south and west of Lafayette. Neighbors are used to seeing Morgan standing before an easel on the roadside, rendering the landscape’s crisp greens and golds into hazy reds and purples.

Our first introduction was via telephone. I interviewed Morgan for an article about the popularity of alternative medicine in the heart of Cajun country—a culture known for its blood-thickening diet of gumbo, dirty rice, and boudin (rice and meat served in a sheath of pig intestine). In 1988, Morgan was diagnosed with cancer and decided after finishing a radiation treatment that he would eat macrobiotically—a traditional Japanese diet that some cancer survivors say has healed them. Morgan credits the diet, in which brown rice is a staple, with helping to keep the disease in remission.

Morgan and his wife of 28 years, Mary, transformed their kitchen into a macrobiotic eatery, buying most of their food from the local health food stores and Asian markets, places Morgan had teased others about shopping in. When I later questioned Morgan about the odd coincidence between his fascination (some call it an obsession) with painting the rice fields and the rice-laden diet that has revitalized him, he said he hadn't thought much about that.

Morgan started painting the rice fields on a regular basis shortly before being hired in 1965 to teach drawing by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (formerly, the University of Southwestern Louisiana). He earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Louisiana State University in 1952. After serving as an assistant supply officer in the United States Air Force during the Korean War, Morgan studied at the Ruskin School of Fine Arts in Oxford, England, from 1954-1957. While at the Ruskin, Morgan discovered that he enjoyed painting rapidly, in an “explosive, gestural way.” Morgan combined this style with that of plein aire, the practice of painting on site, usually outdoors, from direct observation, while he traveled through Europe during breaks from school.

“I called it ‘painting on the run,’ ” Morgan says. “That kind of urgency, that direct kind of engagement is a big part of my work. I hope there is a lot of rhythm and tension in my paintings.”

During the 32 years he taught at the University, Morgan always took the summers off so he could paint the rice fields as they are transformed from the brittle brown imposed by winter to spring’s vivid green to the golden blades of summer rice.

“I get teased a lot because painting on an easel outdoors is not as commonly done as it was one hundred years ago,” Morgan explains. “Some artists say it’s such an archaic thing to be doing, but I couldn’t care less what they think about it, and I don’t care what it means."

Morgan’s obsession with this postage-stamp size area conjures names of other artists entranced by a particular place or subject matter—Paul Cézanne, Georgia O’Keeffe, Claude Monet, Paul Gauguin, Winslow Homer. And just as Cézanne glorified the countryside of Aix-en-Provence and Homer the jagged coasts of Maine, Morgan is immortalizing southwest Louisiana. And for his labors, the 72-year-old Morgan was rewarded by the New Orleans Museum of Art’s Delgado Society when it unanimously selected Morgan as the recipient of its prestigious Distinguished Artist Award for 2000. This newfound fame doesn’t surprise B. F. Lafaye, former director of UL’s University Art Museum. LaFaye credits Morgan with exposing this “tucked away part of the world” to people who’ve never eaten alligator pie, been to a fais-do-do, or sifted through the bayous on a pirogue.

“He’s captured a place that’s hard to capture,” Lafaye says. “He captures the essence of the heat and light of the prairie. It’s uncanny. There’s something about the work that you can almost feel the heat waves and taste the colors.”

It was the colors that grabbed me when I first saw Morgan’s paintings. The electric reds and blues of barns that always only appeared to my less lyrical mind as brown-hued, static structures. Morgan’s loose, rapid brushstrokes convey the inherent struggle of life, the underlying impermanence that all of us fight to forget and to subdue.

The mile-long road that leads to Morgan’s place is lined with a dozen or so houses, many of which sit on concrete pillars above the long grass, keeping their inhabitants high and dry when the floods come to the land in spring and summer. A patch-work dog sits in the middle of the chalky road, immobile until the nose of my car creeps close. The horizon surrounds me. Something about this landscape evokes a primeval feeling. Perhaps it’s the umbrella sky with clouds streaked across it like tattered pieces of cotton, and its blue so bright that I have to squint. Or perhaps it’s the turkey vultures whose circling, black figures remind you of the transience of life. Later, Morgan describes the haunting primitiveness to me: “One can believe that in Louisiana plants and animals eventually become coal.”

Morgan greets me on the walk wearing what must be the outfit that he spends ninety percent of his time in: beige overalls dappled with paint, a straw farmer’s hat, and spotless, sturdy brown leather boots –he tells me they are steel-toed Red Wings. My feet sweat.

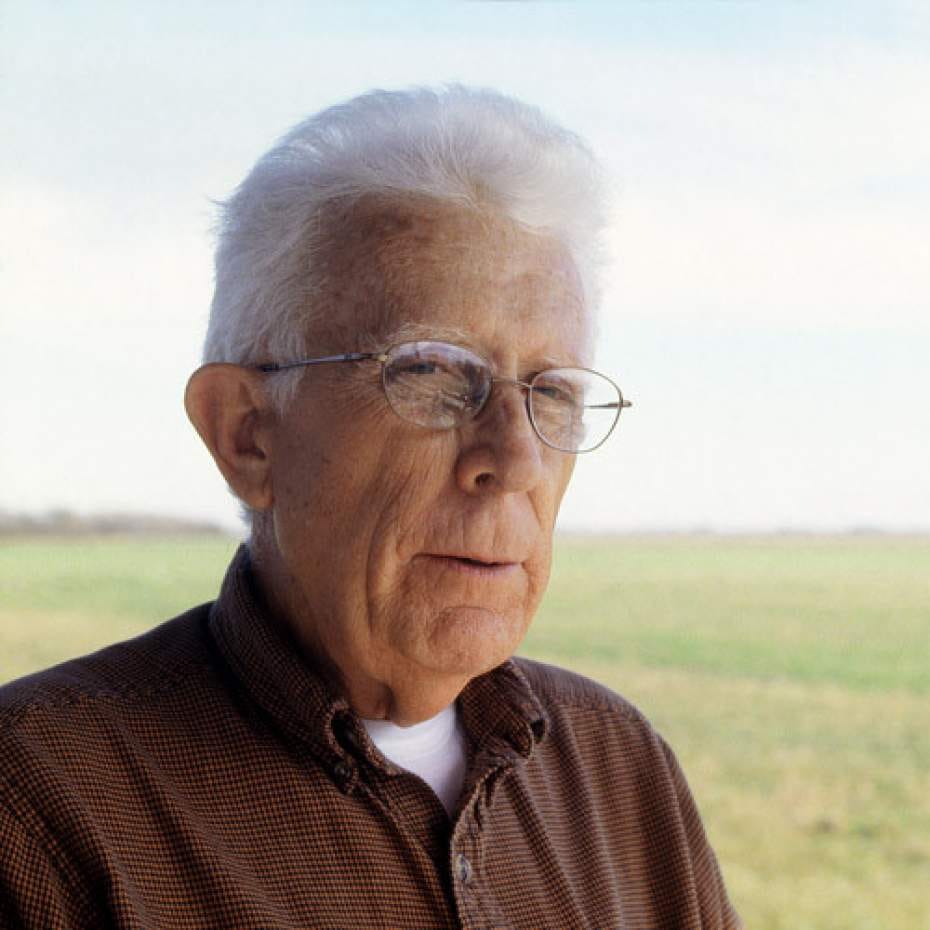

Morgan exudes an easiness, a confidence that comes from the joy of pursuing his life’s dream on a daily basis, and I immediately like him. When he shakes my hand and introduces himself, I find that his voice resembles his appearance—slender and craggy. His words seem to slip off his tongue. His face is handsomely rugged, with thin lips, a long nose, and a jaw as straight and intense as his eyes. Morgan’s white hair and eyebrows complement the blue of his eyes. It’s uncanny that his features reflect those elements he is so often surrounded by, almost as if scraps of sky have colored his eyes and clouds have stained his hair.

“There’s something about this landscape that has infected me since childhood,” Morgan says, his voice lilting as though pushed by a breeze. “It’s mixed and blended, but still very primitive. And I think the wind blows stronger here.”

Morgan’s 1975 Dodge truck rattles like an out-of-whack roller coaster as it bounces along the pocked and graveled roads. We are driving out to his almost-finished studio, which sits on a small hill behind a rice field. His soft voice is swallowed by the asthma-like wheeze of the truck’s engine. Most of its 293,000 miles were racked up driving around what he calls his “magical backyard,” scouting for a place to paint. The jolting prevents me from writing on my notepad, so I switch my cassette recorder on, and hold it close to Morgan’s face.

A thermos of Kukicha twig tea—believed to detoxify the blood —sits in the front seat of the truck, which serves as his portable studio. In its side panels, Morgan carries paintbrushes, acrylic paint, a small folding table, and metal trays he uses as palettes. In the covered bed are two easels, cardboard sheets to protect his paintings, and several Masonite panels. Before Morgan paints on these panels, he cuts them into various shapes—arches, ovals, mushrooms, oblique rectangles—shapes he says are more organic to the painting than the typical square or rectangular canvas. His paintings are rarely framed, and when hung for exhibits, the panels float just inches off the wall. Some critics find the cut panels gimmicky, but Morgan uses the shapes to simulate the “edge of our planet as it meets the sky.”

“When I’m on the prairie, I can almost feel the curvature of the earth,” Morgan says. “There is a pretty open vista out there, and I have a sense of how big the planet is from my small point on it. It really puts me in my place.”

The odd-shaped panels reflect this curvature and often cause the viewer to squint as though he were “peering through a small opening or through a crack in a barn and seeing this enormous vista that lies beyond it,” says Arthur Roger, a New Orleans gallery owner who represents Morgan.

It is Morgan’s use of cut panels that first attracted Roger to his paintings in the early 1980’s. Roger felt then, and still does today, that Morgan’s shaped panels and his expressionistic rendering of the rice fields bring something new to the Southern tradition of landscape painting.

“His obsession with capturing the nuances of every detail of the rice fields, the clouds, the light, and the humidity, and his transporting these large panels outside to paint, all have the makings, to me, of what makes a great artist.”

That said, Morgan’s passion to maintain the integrity of his work has often mildly frustrated Roger. “I constantly would see a painting that I wanted to get into the gallery as soon as possible, but Elemore would wait until the following summer to complete it because the cloud formation in autumn is different,” Roger says. “You don’t get the cumulus cloud formation like you do in the summer. Of course I would think, Well, don’t you remember what they look like?”

Morgan is also an accomplished photographer, a profession his father introduced him to. The senior Morgan was a renowned photographer who captured the poignancy of life in Louisiana’s small towns and rural areas. His last book, The Face of Louisiana, was posthumously published in 1969. The University Press of Mississippi recently published Cajun and Creole Music Makers, a revised edition of the younger Morgan’s 1984 photography book, with text by folklore scholar Dr. Barry Ancelet.

Although Morgan enjoys photography and occasionally will paint from a photograph or a drawing, he is more comfortable painting from direct observation rather than from staring at a photograph or a drawing. For Morgan, the open prairie serves as more than just his studio—it’s a place to worship the encompassing power of nature that has captivated him since childhood. He sees this constant contact with nature as a necessity, and without it, he feels deprived of an essential element in his life.

“As a child, I spent a lot of time out of doors, and I don’t think I’ve ever gotten over that,” Morgan says. “Going through the rice season, attempting each summer to engage actively this natural process, is good for my mental health, regardless of anything else. It occurs to me as an adult, that I am trying to do what I did as a child and get away with it.”

Since our last meeting during the winter months, Morgan had taken a hiatus from painting after he fell in his studio and badly bruised his head. The injury was so severe that Morgan lost his ability to talk and had to have surgery to remove a blood clot. A few months later, Morgan fell asleep while driving home late from a wedding rehearsal dinner. He ended up in the hospital with a few cracked ribs. Although these injuries sidelined Morgan for a while, the only thing he changed about his painting habits was his headgear: he traded his straw farmer’s hat for a bwana’s pith helmet.

He lifts the helmet and taps the side of his head. “I have the leather of an old shoe protecting my skull.”

The studio is near completion now, and it has become the home of two stray dogs and a cat. The feline and her brood of semi-feral kittens live in Morgan’s studio. The patter of paws resounds on the floorboards as the kittens scurry—hidden from sight—through their playground of stacked wooden beams and doors. Morgan salvaged these from his grandfather’s farmhouse and intends to use them in constructing his own home. Outside is the province of the floppy-eared dogs—one tan, the other black—that live in the shade under the studio’s raised foundation. When I drive up the long limestone road to the studio, the dogs race in front of my car, providing me a dusty escort. After their wet and wagged greeting, they plunge into a nearby pond, seeking relief from the late afternoon heat.

As the sun edges near the horizon, I steer my dusty Mazda down the road, following Morgan as he searches for a site to paint. I stare out the window and gaze at the veneer of golden light spread across the rice fields. A moment later Morgan stops the truck. He leaves the motor running as he opens the door and stands on the jamb, one hand to his brow as he looks at the rice field like a safari hunter scouting the grasslands for game. Morgan ducks back into the cab and drives the truck onto the roadside. As I watch Morgan walk to the side of the truck to unload his equipment, I wonder what it is that he sees in this spot.

It is the end of May and the rice fields suggest lush African savannas. The wind sifts through blades of rice, and palm-sized dragonflies float on the current, their tiger-striped wings shimmering in the flaked sunlight. I stand on the edge of the field, among the switchback grass, and stare at the water that curls through the undulating green like a liquid snake. I balance myself, careful not to get my boots wet.

About 20 feet to my left, Morgan stands in front of a long, rectangular panel leaning against two metal easels. On the Masonite are scattered strokes of paint—orange, yellow and red. I close my eyes and breath in the sweet rice smell. I open them hoping to catch a glimpse of the rhythm Morgan feels, of that vibrant spectrum he sees, but is invisible to me. Eyes open, I only see green, brown and gold in the still, grayed twilight.

Before leaving Lafayette, I stop at a mall. I stare at the black-faced directory with its colored lettering and find the store.

The boots fit snugly, and I trace my fingers over the outstretched swan’s wing that’s branded into the smooth, tan leather. I lift my toes against the piece of steel hidden above them. It doesn’t budge.

What a pleasure to time-travel with you back to your visit with artist Elemore Morgan Jr., Rev. Shōren Heather! Thanks for taking us along as you re-visited the day he shared his time with you. (Hurray for your having saved this writing!)