When I first began practicing at the Austin Zen Center in 2001, the teacher mentioned that zazen and the rigors of a monastic schedule were like “putting a snake into a bamboo pole.”

Back then, everything was new, mysterious, and confusing. I didn’t understand what this metaphor meant. Why would you want to put a snake into a bamboo pole? Wouldn’t that hurt the snake? Can’t it just slither out? Fast forward seven years, and this metaphor became my lived reality.

In 2008, I quit my life in Austin and moved to Tassajara Zen Mountain Center as a full-time resident monk. I thought I’d just be there for a six-month sabbatical, and then return to the 9-to-5 world. Instead, my sabbatical morphed into a way of being that infused me with a sense of wonder, gratitude, and freedom. In total, from June 2008 to August 2020, I spent seven years at Tassajara, coming and going several times to Zen centers in Austin, Brooklyn, and San Francisco.

The monastic schedule at Tassajara is relentless, immovable, and impersonal. The more time I spent meditating, chanting, bowing, and eating with everyone in the zendo, the more I began to have a felt sense (embodied experience) of what my first teacher meant by this odd saying.

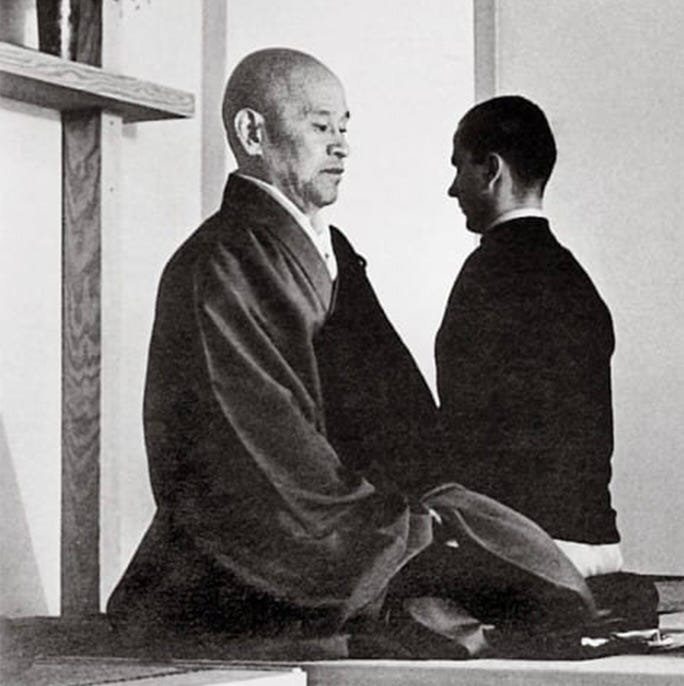

What I came to more fully understand is that the pole represents “things as they are” or to use Suzuki Roshi’s original statement, “things as they is.” I voluntarily slipped into this bamboo pole—although I might have been caught unawares at the time of the slipping!—when I entered the monastery. Being confined in the pole began immediately for us novice monks, who spent the first five days sitting tangaryo: spending about 14 hours a day in the meditation hall. We were well cared for by the resident monks who served us our meals and afternoon tea and cookies. We were exhorted and expected to stay in the cave of emptiness meditating all day, only leaving to use the bathroom or hydrate, and thankfully to sleep at 9 pm.

There are many strategies to survive tangaryo, and the most effective can be summed up in one word: surrender! And by surrender, I mean relax. Relaxing the grip we think we have on reality—letting go of attempting to alter or manipulate what’s arising in the present moment.

If the pole is the reality of the present moment, then the snake represents “me the meditator.” Not only in the physical sense that my body is confined on the cushion or chair; however, and maybe even more importantly, the idea of “me” is confined as well, and this can be very uncomfortable physically and psycho-emotionally.

The pole of zazen and the monastic schedule limit choices and this aids in our noticing when we’re resisting what’s happening. “Resistance” is defined as the “refusal to accept or comply with something; the attempt to prevent something from happening by action or argument.”

The most obvious way the “me” in the pole resists is by moving. Learning how to remain still, open, and alert to what’s happening in the body is perhaps the first “stage”of zazen. We normally don’t speak about “steps” and “stages” in the Sōtō Zen tradition; however, I do feel that becoming attuned to the urge to move helps to illuminate the urge to wiggle and resist mentally and emotionally. Because the pole is so narrow, it is easy to notice that we’re resisting, which is the same as “selfing.”

When we separate ourselves from the one body of the sangha by refusing to follow the schedule, we strengthen the egoic sense of an independent, solid, and abiding “me.” This “me” wants to do its own thing. I am not implying that it’s wrong to want to do what you want to do; however, being in a monastery illustrates how often “doing my own thing” is more akin to being bullied by habitual patterns of thought, word, and deed.

While in tangaryo, the slightest mental wiggling can exacerbate the “regular pain” of sitting still by harming ourselves with the “second arrow”of suffering—all the mental proliferation the mind conjures in its attempt to escape discomfort. Sliding into the bamboo pole of choicelessness—a.k.a., zazen—on a routine basis helps us notice over and over when our attention engages the drama of “me.”

Instead of focusing on the sounds, sensations, sights, tastes, and touches of the present moment, the mind frolics in fantasies and meanders in memories. This delusive thinking is sometimes quite obvious to us while we’re meditating and at other times, it’s so subtle that it lulls us into a false sense of comfort and certainty. “If I just keep thinking this or avoid thinking that, I will be free from pain and suffering.”

Habitual patterns of body, speech, and mind are difficult to investigate and interrupt because they often go unnoticed when we’re caught up in the daily activity of our busy lives. In some ways, we mistake comfort and convenience for freedom, control, ease and certainty. The comforts and conveniences of modern life can often mask psycho-emotional dis-ease. To experience some liberation or spaciousness in our lives, we have to turn toward emotional and physical suffering to become intimate with it.

“The secret of the entire teaching of Buddhism is how to live each moment. Moment after moment we have to obtain absolute freedom, and moment after moment we exist interdependent with the past, future, and other existences. In short, if you practice zazen concentrating on your breathing moment after moment that is how to keep the precepts, to have an actual understanding of Buddhist teaching, to help others, yourself, and to attain liberation.”—Suzuki Roshi, summer 1966

My comfy life before the monastery kept me from noticing the “pole of self” that confined and bullied “me.” Delusive thinking duped me into believing that the more I pursued external, material comforts that expanded my wealth and status, and that afforded me more convenience and leisure, the happier and freer I would feel. Except that wasn’t what was happening. When I closely examined the effect of my success and acquisitions, they didn’t result in more ease or true freedom.

When we let go of the idea of control, the idea of me, our comfort zone expands. We start to see how all of our likes and dislikes—all the conditions we think we need to be happy—are actually what keep us from experiencing being content in the flow of life. Sitting zazen, especially during longer retreats, helps to expand our comfort zone: Our capacity to be okay physically and emotionally with what’s arising; and we begin to find comfort in letting go of thinking we’re in control.

The snake in the bamboo pole eventually stops wiggling, eventually surrenders when she realizes she has no choice, that she’s not in control. If the wiggle of selfing only stops for a moment or two while we’re meditating, that’s a victory!

“Let everything happen to you; beauty and terror, just keep going. No feeling is final."—Rainer Maria Rilke

Excellent message! Excellent writing!