Although I identify as a woman, I’d say that my gender expression is decidedly non-conforming. Back when I grew up in the 1970s and ‘80s, there was not this expansive vocabulary to articulate the fluidity of gender. There was one word for girls like myself, who preferred holding a baseball over a doll, wearing pants over dresses, and scraping knees over having teas.

Tomboy.

This was a decidedly negative term in the working class neighborhood where I grew up. Fortunately, everything changes. Where before there was just the binary boxes of “boy” and “girl” to choose from, now there’s a LGBTQIA+ lexicon to express gender fluidity. In learning more about this vocabulary, I came across a new word that I feel more accurately reflects how I feel about my gender identity and expression:

Demi-girl.

I love this word! It sounds so much more empowering and exciting than the tiresome tomboy trope. It’s not derived from putative masculine qualities: courageous, adventurous, spirited, independent, athletic, etc. It just signifies a person who does not fully fit into the traditional gender box of “woman.”

When I was a child and an adolescent, being a demi-girl just came naturally to me. Just Heather being Heather. Like the Japanese magnolia tree in our front yard that I loved climbing. It didn’t try to shed its gray bark or hide its gorgeous pinkish-white blossoms to look like the row of pine trees that stood soldier-straight along the edge of our yard.

Of course, no one can pinpoint all the causes and conditions that influence our personalities. I had two older brothers, so perhaps I preferred activities that were decidedly in the traditional boy realm because I wanted to be just like them: strong, athletic, and cool. Just like everyone else, I wanted to belong.

My first memory of not belonging happened when I was about five years old. I still vividly recall the incident.

It was a summer morning in the Pocono Mountains, where my family was vacationing. Excited to be in the country, I ran outside the house to play with my eldest brother Anthony, who was 9-years-old. I was most likely clad in a tank top and pants that my mother had made for me. My hair was a very light brown when I was little, so my short, loose curls probably shimmered blonde in the morning sun.

Anthony was standing on the edge of the driveway with a group of boys who were much older than him. Or at least that’s how it appeared to my small self. The boys were standing on the stairs leading to the deck around our house. I was standing on the blue-gray gravel of the driveway looking up at them.

One of the older kids asked if I was a boy. Without hesitating, I said “Yes,” and then a feeling of dissonance waved through me and my voice quavered, “I, I, I mean no.”

My brother and the boys roared with derisive laughter. I froze for a moment while the hot stab of shame pierced my gut and then I turned and ran as fast as I could toward the wooded back yard. I didn’t stop until I was safe among my friends, the pine trees. I don’t recall how long I stood there catching my breath, waiting for the shame to release its grip on me, and hiding from the scorn of the boys.

This is my first memory of experiencing shame, maybe even my first memory of suffering, which the First Noble Truth and The First Characteristic of Existence. My dear Dharma friend Gita Gayatri, who is from India and a Zen priest, told me that dukkha, the Sanskrit word we translate to mean “suffering” or “unsatisfactoriness” can be understood this way:

“Du” means “constricted” and “kham” means sky of consciousness. She says, “When the sky of consciousness is constricted we experience suffering.” The Sanskrit word for “ease” or “bliss” is sukha. Gita says that “su” means “expansive.”

So when the Sky of Consciousness is spacious and expansive, we experience joy and wholeness.

This incident with the boys was the first time I remember feeling that there was something fundamentally wrong with me. This type of shame is what psychologists call “state shame,” a momentary experience that occurs in response to an event. Of course, I had no name for this shame. It was just a body-mind experience of being othered and being ridiculed. I never mentioned this experience to my parents, and this is one of the powers of shame: it keeps us locked in a hell realm where we feel powerless, worthless, and paralyzed.

Unlike my brother and the boys, I was too young to be trapped in the box of the binary gender system. I was still floating in the child-like, non-dual world where trees were my besties, bees hummed in my heart, time was timeless, and unicorns were real.

Of course my brother and the boys responded in this way because of the limited view inculcated in them by the white-bodied, heteronormative, patriarchal world: girls look and dress and behave this way. The approved “gender expression.” Their limited view of girls, limited the view of themselves, shoving them further into the gender box built for little boys. Maybe a box constructed out of the walls of their fathers’ and grandfathers’ suppressed shame?

We know as practicing Buddhists that everything changes. Impermanence is the second of the Three Marks of Existence. So although it was an intense experience of a “state of shame,” it passed through me. However, if we’re routinely shamed by our parents or other authority figures who have power over us, we internalize this shame and it crystallizes into what psychologists call “trait shame.” Shame places our thoughts, words, and deeds (and dress!) into the box of “should” or the box of “shouldn’t.”

This isn’t the shame that keeps us from stealing or lying. This is the shadowy shame that becomes a part of our personality: the karmic conditioned beings that burrow deep into our body-mind and obscure our perceptions of self, others and life. In Buddhism the proximate cause of faith is suffering. The proximate cause is the nearest condition that gives rise to a specific quality. The intense suffering in my life has led to a deep faith in the practice and study of Buddha’s teachings as a path to liberation amid suffering.

I view “trait shame” as the proximate cause of PRIDE. For a person raised as a Roman Catholic, pride was not a cause for celebration because it's one of the seven deadly sins. Given that some religious traditions still consider being queer in all of its glorious manifestations something to be ashamed of, I love that the PRIDE movement transformed this word associated with sin and shame into one used as an expression of our whole selves. Making the invisible, visible in the sunlight of celebration.

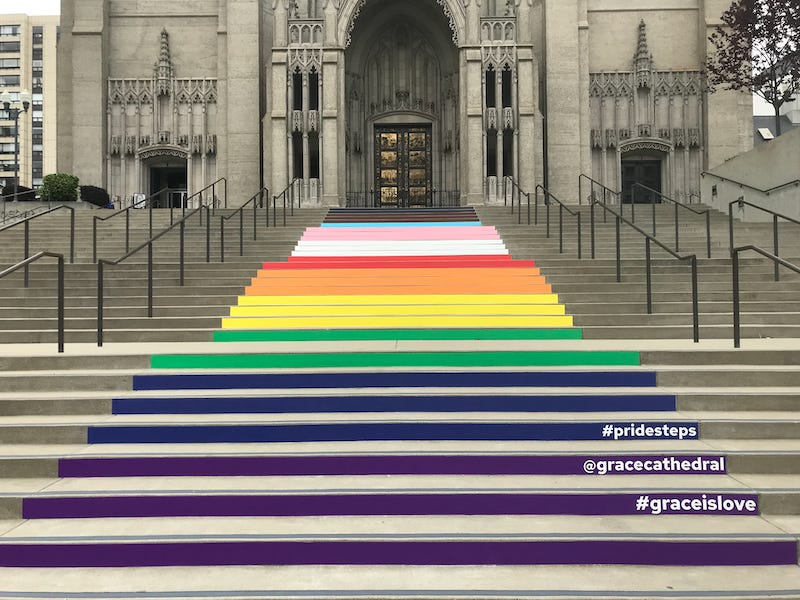

Since it's PRIDE month, and the rainbow flag is the symbol of PRIDE and the LGBTIQA+ community, I’ve been thinking a lot about rainbows. When I was in sixth grade our teacher held up a prism to the sunlight streaming through the window. And POOF! The invisible light magically transformed into streaks of red, orange, yellow, green, blue and violet.

This prismatic moment is akin to how I feel about Buddha’s teachings: Before I began practicing Zen, I perceived my adult self as a solid, independent me, that was separate from nature and everyone else. I didn’t know that my perception and experience of myself as a concrete and discrete entity was a false view. The more I meditated, the more my perception and experience of my self became more ephemeral just like a rainbow. This embodied sense of the fluidity of what I am is the Third Mark of Existence: the “not-self” characteristic.

For me, this is at the same time the most transformative teaching of the Buddha’s and one of the most difficult to understand and experience. One framework the Buddha offered to refract our experience through is the prism of the five aggregates or “heaps”: Forms, sensations, perceptions, formations, and consciousness. The more we practice meditation and study the Buddha’s teaching the more we begin to experience the insubstantiality, impermanence and impersonal nature of these arising mental and physical phenomena.

One definition I find helpful when contemplating this teaching is from the Buddhist scholar Karl Brunholz who says this in his book titled The Heart Attack Sutra:

Not only is our perceiving mind dynamic, in that it changes from moment to moment, but [everything we perceive with our senses is dynamic too]. Phenomena cannot be defined by themselves. Rather we can only talk about them as complexes of mutual relationships with other phenomena, which in themselves are complexes of relationships with other complexes of relationships.

So rainbows, like everything else we perceive and experience, are “complexes of mutual relationships with other phenomena.” This definition of the “not-self characteristic” isn’t as poetic and simple to understand as Suzuki Roshi’s: “Because we are changing moment by moment, I don’t exist.”

And, you know what? Rainbows don’t exist either. They are optical illusions that do not exist in a specific spot in the sky. You can’t touch them or walk under them. They move when you move. When we look at them from the ground, they look like arches or bows. When you’re in an airplane, they appear as circles. They are composed of millions of raindrops that each contribute “rainbow speckles” that refract and reflect sunlight in front of a viewer at an angle of 42 degrees.

The rainbow speckles of our psycho-emotional personalities change every moment because mind consciousness changes every moment. This means that our perceptions are changing each moment, even if we are not attuned to this. Just like seeing sunlight transform into a rainbow shifted my perception of sunlight, my brother and his friends’ reaction to my confusion about my gender also shifted how I perceived myself.

Before our interaction I was not self-conscious of my sex or gender; after they laughed at me, I perceived that there was something wrong with who I was. I went from feeling the expansive joy of Sky Consciousness to the restricted consciousness of the gender binary. Instead of experiencing myself and the boys as an array of rainbow colors, our spectrum of ourselves was reduced to just two colors.

The rainbow flag of the gay pride movement is a symbol of unity and diversity. Out of the invisible, infinite one source emerges the spectacular array of the 10,000 things.

The rainbow flag was first used on June 25th, 1978 for the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade. The first PRIDE marches around the country were held in 1970 to commemorate the Stonewall Uprisings that happened in Greenwich Village in New York City from June 28 to July 3, 1969. Stonewall Inn was a gay bar that was routinely raided by the police. The uprisings are considered the catalyst for the Gay Rights Movement. Although Stonewall is considered the event that launched the PRIDE movement, there were many causes and conditions that led to these riots. In fact, one of the proximate causes was literally just 500 feet away from the Stonewall Inn:

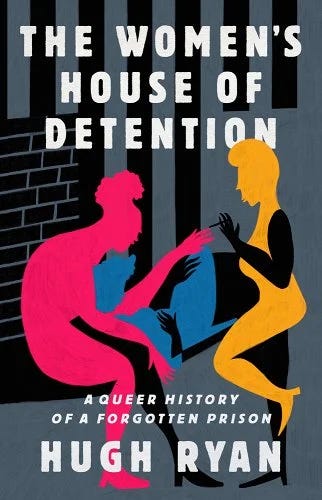

The Women’s House of Detention, which opened in 1932. Tens of thousands of women and trans-masculine people were incarcerated there mostly for being gender nonconforming. By the 1960s, “around 75% of the people imprisoned there were queer in some way,” according to Hugh Ryan, who wrote the book, The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison.

Women and trans-masculine people were arrested for being wayward and dressing incorrectly for their gender. This law, which still exists, was created in the mid-1800s to criminalize people who dressed in costume to protest tax collectors. It states that it’s illegal to dress in costume while committing a crime, however, it’s used to target the LGBTQIA+ community because we love dressing incorrectly for our gender. In fact, the law was also used to arrest protestors during Occupy Wall Street for wearing masks or costumes.

In the 1960s, the Women’s House of Detention began marking gay prisoners with “D” for “degenerate” and placing them in solitary confinement because they were a “danger to other women.” Hugh Ryan says that:

“On the first night of the [Stonewall] riots, people incarcerated in the prison could actually see what was happening out their windows, and they started a riot all their own, setting fire to their belongings and throwing them down to the streets below while chanting “Gay rights! Gay rights! Gay rights!’”

The women’s house of detention was eventually shut down in 1972. And oddly enough, in that same year, the first issue of MS. magazine was published: “A publication for women whose interests went beyond the limits of home and husband,” as an article in the New York Times puts it. The co-founders of the magazine decided to use the title MS. because it described a woman without reference to her marital status. Not surprisingly it was banned from some libraries and newsstands.

I was five years old when the inaugural issue of MS. was published. So I grew up with the word “Ms.” as part of my vocabulary and understood its meaning. The flexibility and fluidity of language emerges from the emptiness of consciousness. The use of the word “Ms.” in lieu of the confining “Mrs.” emerged from the expansive sky consciousness of feminism. This was the beginningless beginning of breaking free from the box of gender roles.

My young nieces are fortunate that they have demi-girl role models in books, magazines, movies, and TV shows. They’re fortunate that there’s so many words to describe the rainbow of gender identities and expressions. This new vocabulary helps me shift my perception not only of myself but of others. Although the words we use to label this and that are empty of any meaning other than the subjective ones we infuse them with, most of us have experienced the harm that words can cause. The ever-expanding vocabulary helps all of us view the world with a beginner's mind (shoshin) where there are many possibilities as Shunryu Suzuki Roshi said.

In one of his fascicles titled “Receiving the Marrow by Bowing,” Eihei Dogen, the 13th century founder of Soto Zen in Japan, chastises male monks who discriminate against female teachers:

“Why are men special? Emptiness is emptiness. Four great elements are four great elements. Five skandhas are five skandhas. Women are just like that. Both men and women attain the way. You should honor the attainment of the way. Do not discriminate between men and women. This is the most wondrous principle of the buddha way.”

And, he also says, “Before becoming free from delusion, men and women are equally not free from delusion. At the time of becoming free from delusion and realizing the truth, there is no difference between men and women.”

This is Dogen’s beginner’s mind in action. Going against the fixed views of women and men and reminding his disciples that the enlightened mind has no characteristics. Zazen helps to cultivate beginner’s mind because we become more intimate with the ever-changing state of our internal world. The more spaciousness we experience with the pleasant and unpleasant experiences that arise through the sense doors, the more spaciousness we have for allowing others to have their own experience and express themselves.

Beginner’s mind is also necessary to investigate our projections and assumptions about other people, especially those who we disagree with or hold ill will toward. No matter someone’s political beliefs, religious traditions, or cultural heritage, we all experience suffering. We all are trying to find happiness and contentment. We’re all trying to care for our family and friends. If our practice doesn’t extend the rainbow as a bridge to all sentient beings, then we are stuck in the binary box of “us vs. them.”

There are many myths about rainbows in different cultures. Some view them as serpent-dragons that are evil and dangerous to humans. Some view them as a belt of heaven or God. One particularly pertinent and fascinating myth is that rainbows are androgynous—that they represent and possess female and male qualities. The other myth that I came across that’s common to countries as diverse as Bulgaria, Serbia, Australia, Greece, and Sub-Saharan Africa is that if a person jumps over a rainbow or walks under one, they’ll be transformed from a boy to a girl or a girl to a boy. These myths remind me that when we solidify our perceptions of others, we solidify our perceptions of ourselves.

Zen is a practice of moving beyond the binary and manifesting the mystery.

As

says, “Zen is for those who thrive on the intangible, the ambiguous, the amorphous, and the infinite. We are stars forever suspended in nowhere. You can’t really see Zen. You can only experience it after some time of walking the path.”I hope that as we continue on this path, we walk side-by-side under many, many rainbows forever suspended nowhere.

Thank for this piece. I love this reflection on rainbows!