Dear Spark Zen Readers, I hope you’re doing well today. Below is the first chapter of

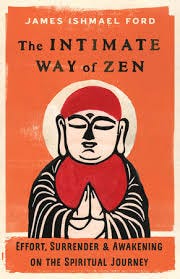

’s newest book The Intimate Way of Zen, which you can preorder at Shambhala for a 30% discount; use code IWZ30. James recently launched his own Substack . Thank you James for permission to reprint this first chapter. Peace + Bows from the mountain valley, Rev. Shōren HeatherBlessed are they who cease to grasp, who let go of hatred,

and are no longer swayed by siren songs of certainty.

Who now find delight in the flowing currents of their lives

from dawn and through the night.

They are like trees planted by deep springs,

they bear fruit in season.

Their lives evergreen,

their words and actions healing the world.—Psalm one [i]

“Entering the Intimate Way”

(Oxherding 1)

I used to have strong views about what it takes to establish a Zen meditation practice.

For many years when I led introductions to Zen or taught Zen meditation classes, I’d ask people why they came. A lot of them had heard meditation was good for their mental health. People wracked with anxiety heard that meditation could lower their blood pressure. All in all, meditation was said to lead to a general sense of well-being. And indeed, Zen meditation and similar practices of silence and presence are associated with some physiological shifts, including lowering blood pressure. Additionally, these practices can prove a valuable adjunct to psychotherapy. Over the years I have encouraged any number of people to seek the potential complementary benefits of therapy and meditation practices.

And. A simple cost-benefit analysis suggests that practicing Zen to improve your health isn’t necessarily the smartest way to go. For instance, I’m pretty sure one can achieve similar results to a half hour of meditation by playing with a cat, petting a puppy, or taking a long walk. Which, frankly, sounds an awful lot more fun than witnessing the rising and falling of one’s thoughts and feelings. A friend once observed how “there could even be a Zen teaching somewhere along the line in playing with that cat.” All without the sore knees.

As the Korean Zen master Seung Sahn once said, “Zen is boring.” Hard. Boring. Sore knees. Sore backs. Some very unpleasant inner psychological encounters. When we’re just looking to feel a little better, perhaps Zen isn’t the best thing going.

Or so it seemed to me when introducing people to the practice. Gradually, however, I realized I was missing a pretty important point. What I began to notice as I kept asking my question of those seeking instruction —“What brought you here?”—was that perhaps there isn’t actually some “right” motivation. People presented with all manner of reasons for their presence in my class or meditation session, and I could never tell who would or wouldn’t stick around. Perhaps, in the final analysis, no one actually has a “good reason” for embarking on the spiritual quest, whether Zen or any other. Or, maybe any reason might be good enough.

Our motives for taking up any spiritual practice are always clouded. And those motives change over time. In our human hearts, motivations almost always have multiple causes. Some we know about. They’re what we think is why we do something. But, as with the proverbial iceberg, our deeper motivations are elusive, even to ourselves. A simple example is trying on Zen because of a deep spiritual longing, but also noticing that really nice-looking person seems to go to the meditation center, as well. And even in that example, what is really the leading reason?

Many years ago, my brother and I took a hike in the mountains above Palm Springs. We met some other hikers and at dusk we set out our sleeping bags near each other. All of us shared wine and cheese and bread and some fruit we’d packed in with us. Then in the middle of the night it started raining. It quickly became dangerous. We all scampered up the side of the gully, and no sooner than we were as high as we could get did we hear the water rushing down, a torrent. It was terrifying. Our companions began to cry out to God to save them. One loudly promised to change and to become God-fearing if he were saved.

The truth is, I have no idea what came next for him. Most likely, given my observation of humans, is that by the next morning he’d completely forgotten his loud and fervent prayer. But for some people—and I’ve met them—that promise is kept. They continue on. Some for a lifetime. So, who’s to say that a sudden, desperate plea to God to save one’s life is not a perfectly good reason to start upon a path of spiritual transformation?

But if our precise stated motive for entering the path does not matter, or doesn’t matter as much as might think it would, there is something that does matter. It is as old as our human existence. In my years as a Zen teacher and Unitarian minister, I have detected a pattern underneath all that variety in peoples’ stated reasons, something I now consider the most fundamental of all our motivations for spirituality or religion—noticing that there’s something wrong.

Noticing a sense of wrongness is the first of three critical factors in how the spiritual path mostly opens for people, the other two being the discovery of a hope and then the setting of an intention. But let’s stick with that sense of wrongness for a bit longer. We can see that “wrong” in a hundred different ways. The wrong, in fact, seems specifically cut for each of us. There are a lot of words for this sense of wrongness: unease, alienation, despair. And it becomes tied up with a longing. It can be like finding a hole in the heart. Me, I felt a lack. I had the sense of wrong. I could see the hole in my heart, but I didn’t have all that much faith there was a fix.

When I was thinking about entering a Zen monastery, I was—and perhaps I remain—one of those of little faith. Later there would be a finding of how doubt and faith are facets of something rather larger. Right here at the beginning, well, Thomas wanting to poke his finger into the wounds was my patron saint. But that’s for later. At the time I was driven by a desperate feeling that things were not right, and so even though I was filled with doubt, it seemed all I needed was the tiniest modicum of belief that something good might come of turning myself over to Zen. Here, the verse for the first of the Ox Herding Pictures sings to me as it has to so many seekers over the centuries:

Wandering in the wilderness, lost, I continue searching.

The waters rage, I wander into the mountains, following the trackless path;

Exhausted and despairing, I don’t know where to go.

I only hear cicadas singing among the trees.[ii]

I know this place. And perhaps you do, as well. However we might frame it, that feeling something’s not right is the spur that starts us on the way. There is no correct or incorrect choice of name for this sense. What it is we notice specifically in our lives is ours. It is my feeling or your feeling that there’s something wrong in the world. Your problem, your sense. My problem, my sense. Or, perhaps, we begin to notice it’s something wrong in my heart, in your heart – which is the beginning of a beginning.

That mustard seed.

And immediately with that sense of wrong, there is a rising sense there is a right. We almost certainly can’t put a word to what the right is. Only that with a wrong, a right should, or at least might, be able to follow. Call it a hunch. It’s found in how our human brains work.

In the Buddhism of the Great Way, the Mahayana, this sense, this hunch, is called Bodhicitta. In Sanskrit, Bodhi means “awakening” and Citta means “that which is conscious,” so Bodhicitta is usually translated as the mind of awakening. Whatever we call that hunch, the mustard seed begins to sprout, and thus we find the second critical factor in embarking on a spiritual path—the discovery of a hope.

Here is the most natural of all natural experiences. In the midst of our suffering, our longing, our desperation, we capture a glimpse. Or, really, something touches us. And with that, if we are lucky and really notice some movement of some spirit within us, we turn our attention to the intimate way.

And it is with this that I think of those who in the midst of some terrible fix call out to God and make a promise. In the heat of disaster, they call on God. They call on Guanyin. They call on Mother Mary. They call on their own mother.

“They.” You know. You. Me. Us.

And in that crying out, sometimes a promise is made—the setting of an intention. And this is the third thing.

As I age, I find myself interested in the Pure Land. (Apparently, this broadening of focus into the Pure Land is not uncommon among aging Zen priests and teachers.) Although there have been many Pure Lands to which Mahayana Buddhists have aspired over the centuries, the most common is that of Amida, a Buddha from somewhere far away from our time and place who makes a vow to save all beings. By putting your trust in Amida’s vow, you are brought to a realm where awakening is easy—to the Pure Land. Some would say that place given by another, and the place achieved by the hard work of Zen practice, are the same.

But the critical point, as I see it, is in fact the vow itself. It is noticing something is wrong, feeling there can be a right, and making a promise to pursue that right.

This occurs in many ways in different cultures and religions. We see it ritually in the adolescent rite of passage, from Bat and Bar mitzvas within Jewish communities, to the confirmation rites of many Christian denominations, to the “adult” baptism of my childhood religion. In these cases, it is often part of a larger pattern that is more observed in the breach than as an authentic motion of the heart. But, even latent, it can have power.

I think that the third step in Alcoholics Anonymous is a frank and clear expression of the power of vow. One is invited to make “a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we [understand] him.”[iii] (Him, her, them, it. I gather the range of placeholders for the mystery that works within the steps is vast.)

Among many cultures the active making of an intention, and stating it, is seen as initiation.

We in the Zen schools call it the original vow and usually frame it with four parts.

In the standard translation of the Sotoshu, the official Japanese Soto Zen church, the four vows are:

Living beings are limitless; I vow to deliver them.

Mental afflictions are inexhaustible: I vow to cut them off.

Dharma gates are incalculable; I vow to practice them.

The buddha way is unsurpassed; I vow to attain it.[iv]

In the Boundless Way and Empty Moon Zen communities we say:

Beings are numberless, I vow to free them;

Delusions are inexhaustible, I vow to end them;

Dharma gates are boundless, I vow to enter them;

The Buddha Way is unsurpassable, I vow to embody it.[v]

The Pacific Zen Institute offers another version, one that I really love.

I vow to wake the beings of the world.

I vow to set endless heartache to rest

I vow to walk through every wisdom gate

I vow to live the great Buddha way.[vi]

I have reservations about how the second line in this version, which is specifically about the source of our hurt as an endless grasping, jumps to the inevitable experience that rises from grasping. Yet I still find this version enormously compelling. It feels such a pure expression of some ancient vow.

Each of these versions, I believe, captures the essential elements of that primordial, primary vow. To notice there is hurt. To notice how that hurt is found within an incorrect appreciation of our place within the world. To desire to bring healing to the matter. And to begin and end knowing this is in fact a family matter.

It’s all captured for us in that image of the Ox Herding cycle. Of someone wandering, lost. The world is confusing, haunted, and very, very dangerous. It really feels like a trackless path. At best there are the cicadas calling, maybe a crow cawing. Calling to us.

The world itself, presenting.

With this noticing and this promise made to ourselves, and on behalf of the whole hurting world, we discover we’ve entered the intimate way.

[i] Author’s version. The first psalm is a wonderful summation of the spiritual path and its goal. Which might be lost in the original framing. Sometimes scholars classify the first psalm among the “wisdom literature.”

[ii] Author’s version. An online version of the images and commentaries, with links to others, is available here: John M. Koller, “Ox-Herding: Stages of Zen Practice,” Expanding East Asian Studies website, accessed June 2, 2023, http://www.columbia.edu/cu/weai/exeas/resources/oxherding.html.

[iii] “The Twelve Steps,” Alcoholics Anonymous website, accessed June 2, 2023, https://www.aa.org/the-twelve-steps.

[iv] https://www.sotozen.com/eng/practice/sutra/scriptures.html page 74

[v] https://www.emptymoonzen.org/liturgy/ page 1

[vi] https://www.pacificzen.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/SUTRA_TextsandService.pdf page 14

What a refeshing read! Thanks for sharing this with us, Heather. I have seen this sense of "not quite rightness" lead folks to practice. Many people I've known, myself included, had a profound experience of impermanence that led them to Buddhism, having found that something they had counted on and believed in had been suddenly whisked away. "Painted cakes don't satisfy."

Such a pleasure to read this with its clarity, humanity, and gentle humour, too. I followed the link to art (and lovely short blogs*) by Seigaku Amato, Osho: it is as strong and appealing as JIF's prose style, making them a good partnership. [https://seigakuamato.com/art]

Thanks to you, Heather, and to JIF for offering this excerpt to us. I already had 'The Intimate Way of Zen' on my amazon canada wishlist. Now, I've just pre-ordered it. July 23/24 is not as far off as it feels!

Still humming in my head is the last bit of this shared chapter:

"... Each of these versions, I believe, captures the essential elements of that primordial, primary vow. To notice there is hurt. To notice how that hurt is found within an incorrect appreciation of our place within the world. To desire to bring healing to the matter. And to begin and end knowing this is in fact a family matter.

It’s all captured for us in that image of the Ox Herding cycle. Of someone wandering, lost. The world is confusing, haunted, and very, very dangerous. It really feels like a trackless path. At best there are the cicadas calling, maybe a crow cawing. Calling to us.

The world itself, presenting.

With this noticing and this promise made to ourselves, and on behalf of the whole hurting world, we discover we’ve entered the intimate way."

*

*Among the Dharma Blogs I read by Seigaku Amato today, one rang a special bell for me: "Nothing Special Lineage" -- eased an knot in my heart about our human competitiveness arising naturally even in buddhism. To borrow Laura B's word from her post here -- refreshing as can be.