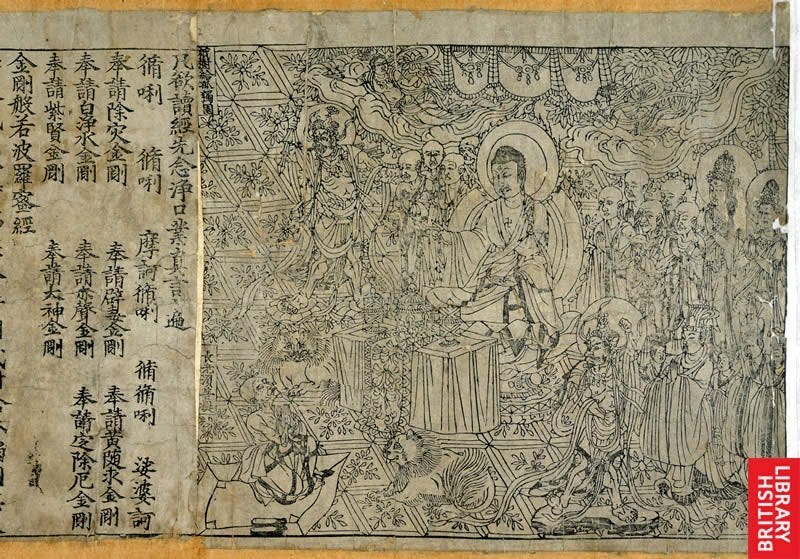

In 1900, a monk named Wang Yuanlu in Dunhuang, China, discovered 40,000 ancient scrolls, manuscripts, paintings, and other artifacts hidden in “The Cave of a Thousand Buddhas”—a Silk Road outpost near the Gobi Desert. This cave library had been sealed around the beginning of the 11th century to protect it from being raided. The Diamond Sutra, a Sanskrit text translated into Chinese, was among these ancient documents. 1

This sealed, hidden cave was among 492 caves carved out of a long cliff wall in the present-day province of Gansu in Northwest China. This holy site, called the Mogao (or ‘Peerless’) Caves, was a major Buddhist centre from the 4th to 14th centuries. Thousands of documents were stolen from the cave and smuggled to England in 1907 by British-Hungarian archaeologist Marc Aurel Stein. The International Dunhuang Project is now digitizing those documents and 100,000 others found on the eastern Silk Road.2

Carved into the cliffs above the Dachuan River, the Mogao Caves south-east of the Dunhuang oasis, Gansu Province, comprise the largest, most richly endowed, and longest used treasure house of Buddhist art in the world. It was first constructed in 366AD and represents the great achievement of Buddhist art from the 4th to the 14th century. In Sanskrit, the title is: Vajracchedika Prajnaparamita, which is translated as: “The Perfection of Wisdom which cuts like a thunderbolt.” Vajra means “thunderbolt” or “diamond,” and this “diamond wisdom” cuts through delusion to reveal the truth of Buddha Nature. Prajnaparamita means the “perfection of wisdom.”

The Diamond Sutra is part of the Prajnaparamita literature, which “are a body of self-consciously related works dealing with the subject of the new prajna, or “wisdom,” taught by the Mahayana. Instrumental in the origins of the Mahayana itself, some texts from this category are among the earliest Mahayana sutras, probably originating in the 1st century BCE [Before the Common Era].”3

According to the Buddhist scholar and former Korean Zen monk Mu Soeng, the title can also be understood as: “ ‘sharp like a diamond, which cuts away all unnecessary conceptualization and brings one to the further shore of awakening.’ . . In the days before machines, jewelers used diamonds to cut glass and other jewels. It is in this sense of prajna wisdom cutting through all delusions that the term diamond cutter is employed in the title of the sutra.”4

“A relatively short text, the Diamond Sutra consists of thirty-two short chapters presenting a dialogue between the Buddha and his disciple Subhuti, centered primarily on the twin themes of emptiness and the path of the bodhisattva. It enumerates the six perfections of the bodhisattva path but focuses on the perfection of wisdom.” 5

“The first noteworthy association we have of the Diamond Sutra with the Zen tradition is through the life of Hui-neng, the sixth [ancestor], considered the real founder of the distinctly Chinese Zen tradition. Whether legend or fact, the story of Hui-neng says that as a young boy he lived in extreme poverty and gathered wood to sell in the market to support himself and his mother. One day, in the marketplace, he heard a monk chant a phrase from the Diamond Sutra that said, ‘Let your mind function freely, without abiding anywhere or in anything.’ Upon hearing this phrase, the young boy was suddenly enlightened!”6

“A distinctive feature of Prajnaparamita-inspired wisdom is the awareness that language is inadequate to express the insights of an awakened consciousness that has managed a total extinction of the ego-self either through cognition (as in the case of Hui-neng) or through sustained meditational effort (as in the case of yogis.) The Diamond Sutra’s use of language to destroy linguistic categories is intended to produce liberated cognition and finds parallel in modern deconstructionism.”7

“The Zen tradition has tried to comprehend this wisdom [of non-duality via non-conceptualization] through the now formalized teaching of not-knowing. Not-knowing is the intuitive wisdom where one understands information to be just that—mere information—and tries to penetrate to the heart of the mystery that language and information are trying to convey. . . . In our ignorance, we treat these units of information as self-evident truths and fail to investigate our own experience directly. The not-knowing approach is not a philosophical or intellectual entertainment: it is a doorway to liberation.”8

The last verse of the Diamond Sutra is often quoted and memorized as a pithy and poetic reminder of the teachings of emptiness and impermanence:

So you should view this fleeting world—

A star at dawn, a bubble in a stream,

A flash of lightning in a summer cloud,

A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/Five-things-to-know-about-diamond-sutra-worlds-oldest-dated-printed-book-180959052/

Ibid.

Skilton, Andrew. A Concise History of Buddhism. Birmingham (England), Windhorse Publications, 1994.

Soeng, Mu. The Diamond Sutra. Somerville, MA, Wisdom Publications, 2000.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.